AFED #51: Císařův slavík [The Emperor's Nightingale] (Czechoslovakia, 1949); Dir. Jiří Trnka

Jean Cocteau once said of the Czech animator Jiří Trnka that "the very name conjures up childhood & poetry". Sadly to most people the Trnka's name is only likely to draw a blank expression, but in animation circles his standards of excellence once drew comparisons with Disney.

The son of a plumber, Trnka first achiewed renown as a painter and childrens' illustrator and didn't begin animating until the age of 33. His earliest shorts were cell-based, but it was with stop motion, or puppet animation, that he emerged as an original voice, adapting the distinctive style of his illustrated work to the three dimensional medium.

With Czechoslovakia now under Communist rule in those post-war years, animation enjoyed state patronage and a degree of creative freedom not allowed to feature films with their wider audiences. Unlike the industrialised production methods of Disney et al, Trnka worked in a small studio, personally supervising the entire process. His work incorporated a breadth of subjects; from traditional tales of village life in The Czech Year (1947) to cowboys and Indians in Song of the Prairie (1949).

Probably his best known work, an adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen's The Emperor's Nightingale received widespread distribution in the West in 1951, with Boris Karloff lending his rich, paternal tones in an English voiceover. Strangely, this is the second Sunday running I've found myself reviewing an Anderson adaptation from across the Iron Curtain, following The Tinderbox, but while that film was kitsch, there's no mistaking Trnka's class.

Aside from a live action framing sequence about a lonely young boy, it's a faithful adaptation of the original story. A pampered Emperor hears of the beautiful singing of the nightingale and decides he wants one of his own, discards it when a new novelty comes along, then realises the error of his ways.

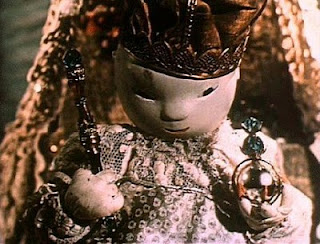

The puppets are exquisitely crafted; their subtle features evocative of oriental art. As with all his work, facial expressions are less important than the choreography of the figures and the subtle use of camerawork to communicate meaning. The set designs are sometimes ornate and detailed, on other occasions abstract and expressionistic. Trnka is quite capable of showing off his virtuosity, but the story always takes priority.

Naturally, in an age of computer generated visuals there's something rather quaint about this technique. Probably if Trnka were working today he'd work in that medium himself, but the fundamentals of visual narrative remain the same and it would be interesting to see how the film played with a contemporary juvenile audience. My own thinking is you don't need a rapid, kinetic style to capture the imagination; though given the absence of any alternative in modern cinema you'd be forgiven for thinking so.

The son of a plumber, Trnka first achiewed renown as a painter and childrens' illustrator and didn't begin animating until the age of 33. His earliest shorts were cell-based, but it was with stop motion, or puppet animation, that he emerged as an original voice, adapting the distinctive style of his illustrated work to the three dimensional medium.

With Czechoslovakia now under Communist rule in those post-war years, animation enjoyed state patronage and a degree of creative freedom not allowed to feature films with their wider audiences. Unlike the industrialised production methods of Disney et al, Trnka worked in a small studio, personally supervising the entire process. His work incorporated a breadth of subjects; from traditional tales of village life in The Czech Year (1947) to cowboys and Indians in Song of the Prairie (1949).

Probably his best known work, an adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen's The Emperor's Nightingale received widespread distribution in the West in 1951, with Boris Karloff lending his rich, paternal tones in an English voiceover. Strangely, this is the second Sunday running I've found myself reviewing an Anderson adaptation from across the Iron Curtain, following The Tinderbox, but while that film was kitsch, there's no mistaking Trnka's class.

Aside from a live action framing sequence about a lonely young boy, it's a faithful adaptation of the original story. A pampered Emperor hears of the beautiful singing of the nightingale and decides he wants one of his own, discards it when a new novelty comes along, then realises the error of his ways.

The puppets are exquisitely crafted; their subtle features evocative of oriental art. As with all his work, facial expressions are less important than the choreography of the figures and the subtle use of camerawork to communicate meaning. The set designs are sometimes ornate and detailed, on other occasions abstract and expressionistic. Trnka is quite capable of showing off his virtuosity, but the story always takes priority.

Naturally, in an age of computer generated visuals there's something rather quaint about this technique. Probably if Trnka were working today he'd work in that medium himself, but the fundamentals of visual narrative remain the same and it would be interesting to see how the film played with a contemporary juvenile audience. My own thinking is you don't need a rapid, kinetic style to capture the imagination; though given the absence of any alternative in modern cinema you'd be forgiven for thinking so.

Comments

Post a Comment