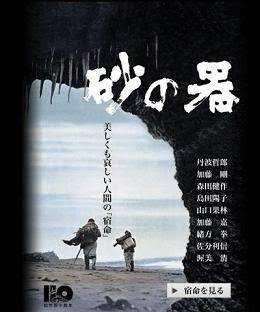

AFED #45: Suna no utsuwa [Castle of Sand] (Japan, 1974); Dir. Yoshitaro Nomura

As a rule most films stick to a particular pitch or tone when telling a story. The pacing may rise or drop, there may be quirks or twists, but you can usually be fairly confident what kind of film you're watching after the first five or ten minutes.

Even when the script takes a detour into the strange its usually given some kind of foreshadowing. But when the style suddenly shifts dramatically our fondest held notions of classical aesthetics are rather rudely challenged. Imagine you were watching a stirring account of the brutality of trench warfare in 1917 when an hour into the film without explanation a talking panda suddenly turns up in a time machine. You'd feel perplexed, perhaps even a little angry.

Granted, if you'd heard or read about what to expect beforehand it might not be such a surprise, but that was almost how I felt when watching Yoshitaro Nomura's Castle of Sand. It's a film that moves the goal posts a couple of times during its 142 minutes and consequently left me more bemused than affected.

Apparently considered one of the classics of Japanese cinema, I'll confess to never having heard of Castle of Sand until a couple of weeks ago; an interesting example of how well-regarded products of a national cinema can miss out on wider distribution or recognition. This was one of several films the prolific Nomura adapted from the popular novels of Seichō Matsumoto, but it's the structural approach that makes it so distinctive.

It begins as a dry police procedural story as two Tokyo cops - the traditional senior/rookie combo - begin probing the murder of an old man. Following up the sparsest of clues into rural backwaters, it's only when the victim is finally identified as an ex-policeman that they start to make significant headway.

The dynamic shifts when their investigations become intercut with scenes the life of a famous contemporary composer, who the cops had seen during a train journey earlier in the film and has some tenuous connection with the dead man. A pretentious and unsympathetic character who's writing a piano concerto while having affairs with two women (one the daughter of a minister) you don't need to be a genius to realise he's somehow implicated; the question is 'why?'.

Answers come in the last forty minutes and a totally unexpected change in style. As the cops prepare to make their arrest we learn in a flashback sequence about the composer's tragic childhood. Played out without dialogue to music from the composer's concerto as he gives his debut performance, this incongruous melodrama seems to belong to a completely different film.

Even the reaction of the cops as they recount their evidence becomes bizarrely overwrought. Depending on your perspective it's either an inspired juxtaposition of different genres or clumsy and contrived storytelling. The same information could have been imparted without the reductio ad absurdum, so one wonders what the point was.

Castle of Sand may be a film that improves on repeat viewings when the surprise factor of the style shift is removed from the equation. On the other hand the novelty value may be the only thing in its favour. Personally I came away thinking this is a film that has probably been overlooked with good reason.

Even when the script takes a detour into the strange its usually given some kind of foreshadowing. But when the style suddenly shifts dramatically our fondest held notions of classical aesthetics are rather rudely challenged. Imagine you were watching a stirring account of the brutality of trench warfare in 1917 when an hour into the film without explanation a talking panda suddenly turns up in a time machine. You'd feel perplexed, perhaps even a little angry.

Granted, if you'd heard or read about what to expect beforehand it might not be such a surprise, but that was almost how I felt when watching Yoshitaro Nomura's Castle of Sand. It's a film that moves the goal posts a couple of times during its 142 minutes and consequently left me more bemused than affected.

Apparently considered one of the classics of Japanese cinema, I'll confess to never having heard of Castle of Sand until a couple of weeks ago; an interesting example of how well-regarded products of a national cinema can miss out on wider distribution or recognition. This was one of several films the prolific Nomura adapted from the popular novels of Seichō Matsumoto, but it's the structural approach that makes it so distinctive.

It begins as a dry police procedural story as two Tokyo cops - the traditional senior/rookie combo - begin probing the murder of an old man. Following up the sparsest of clues into rural backwaters, it's only when the victim is finally identified as an ex-policeman that they start to make significant headway.

The dynamic shifts when their investigations become intercut with scenes the life of a famous contemporary composer, who the cops had seen during a train journey earlier in the film and has some tenuous connection with the dead man. A pretentious and unsympathetic character who's writing a piano concerto while having affairs with two women (one the daughter of a minister) you don't need to be a genius to realise he's somehow implicated; the question is 'why?'.

Answers come in the last forty minutes and a totally unexpected change in style. As the cops prepare to make their arrest we learn in a flashback sequence about the composer's tragic childhood. Played out without dialogue to music from the composer's concerto as he gives his debut performance, this incongruous melodrama seems to belong to a completely different film.

Even the reaction of the cops as they recount their evidence becomes bizarrely overwrought. Depending on your perspective it's either an inspired juxtaposition of different genres or clumsy and contrived storytelling. The same information could have been imparted without the reductio ad absurdum, so one wonders what the point was.

Castle of Sand may be a film that improves on repeat viewings when the surprise factor of the style shift is removed from the equation. On the other hand the novelty value may be the only thing in its favour. Personally I came away thinking this is a film that has probably been overlooked with good reason.

Comments

Post a Comment